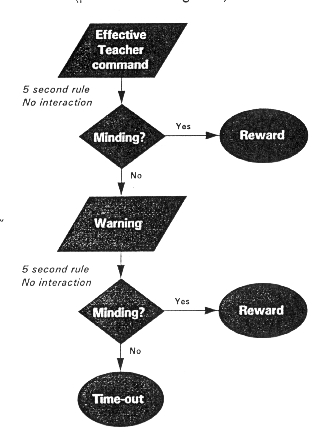

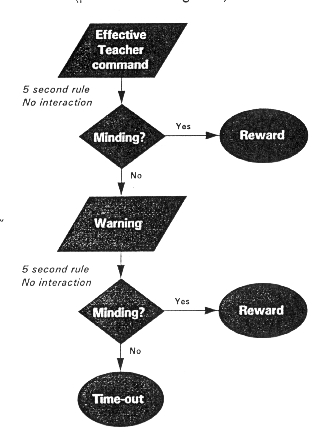

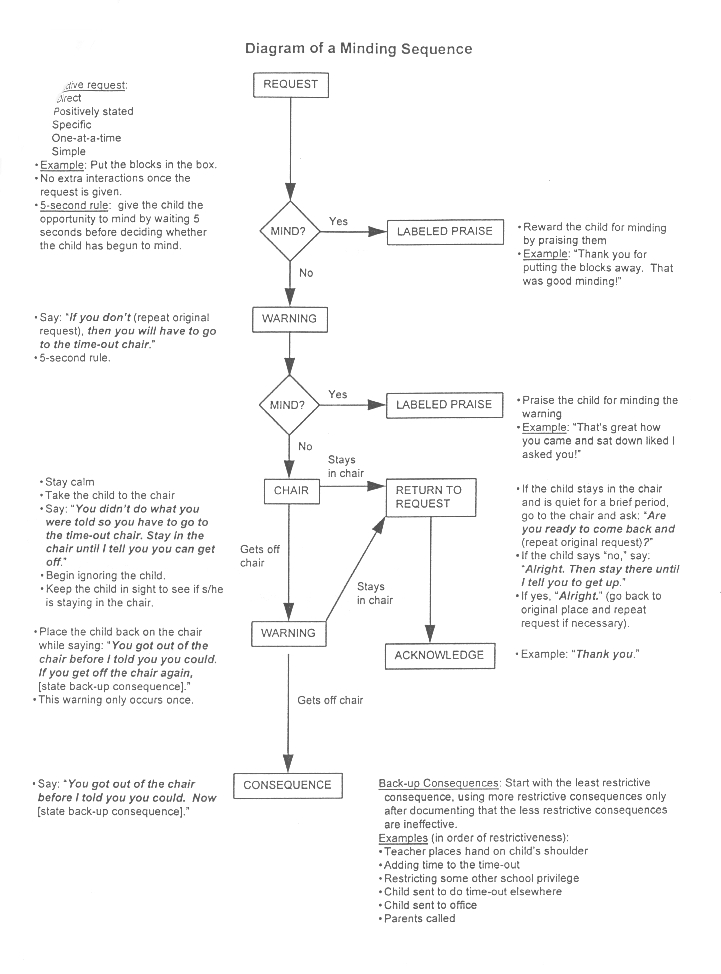

Once

it is decided to send a child to time-out, communication should be brief,

clear, and direct. See the charts below for examples of effective

communication.

Once

it is decided to send a child to time-out, communication should be brief,

clear, and direct. See the charts below for examples of effective

communication.

Time Out

in the

School Setting

(Antecedent Interventions)

Classroom Interventions for Children with Attention Deficit

Disorder

Description:

Time out is a punishment proceedure that involves the withdrawal of positive reinforcement as a consequence of inappropriate behavior. Time-out has been recommended for children as old as 9 to 10 years of age. The effectiveness of time-out in reducing imappropriate behavior is well-documented; however, the proceedure has been somewhat controversial die to its potential for misuse (Abramowitz & O'Leary, 1990). Most concerns about time-out are related to the restrictiveness of the proceedure; however, the degree of restrictiveness varies with the type of time-out proceedure used. The least restrictive forms of time out are those that do not involve exclusion or isolation. Examples of such nonexclusionary forms of time-out include: having the children put away their work for a time (which eliminates the opportunity to earn rewards for academic performance); the temporary removal of rewarding materials, such as taking away art materials; or having the children put their heads down on their (which reduces the opportunity for engaging in social interaction) (Barkley 1990).

A more restrictive time-out proceedure involves excluding a child from classroom activities by placing a child in a designated area for a period of time while attention and other rewarding activities are withheld. This may involve having the child sit in a chair facing a wall. The most restrictive time-out proceedures involve removal of a child to an isolated room. In most schools, the principal of least restriction should be followed when selecting a time-out proceedure, starting with the least restrictive proceedure, and moving to the more restrictive proceedures only after the others have been ineffective. To ethically and effectively implement isolatioin forms of time-out in the classroom, the following guidelines are recomended (Abramowitz & O'Leary, 1991).

|

* Prior to implementing time-out proceedures that involve isolation, techniques for increasing appropriate behaviors and other punishment proceedures that are less restrictive than isolation time-out should be properly implemented for a time and documented. * Staff must be fully trained in

the proceedure and physically capable of carrying

* Both the target behaviors and the

specific time-out proceedures should be

* Determine how noncompliance to

the time-out proceedure will be dealt with in

* Information on the level of target

behaviors prior to implementing time-out and

* Each time-out should be recorded.

|

Advantages:

The effectiveness of time-out in reducing inappropriate behavior is well-documented. Time-out has been shown to be an effective component of an overall behavioral plan to reduce noncompliance and aggression. An additional advantage to time-out is that it is a punishment technique that can be administered immediately. Behavioral techniques, which can be administered as close to the behavior as possible, are appropriate for younger children and children with ADD.

Limitations:

Time-out is a highly technical proceedure that is difficult to implement properly. There many way that time-out can go wrong and become less effective. Time-out operates on the assumption that the activity that is withheld from the child is rewarding. Teachers should be careful that the child is not avoiding some unpleasant activity by going to time-out. For example, going to time-out for not staying on-task during independant math work actually may be preferable to doing math work to a child who dislikes math. Due to its restrictiveness and difficulty in implementation, time-out should be reserved for intervention with the most disruptive and unacceptable behaviors and only with staff that are trained in how it is properly used (Abramowitz & O'Leary, 1991).

A second limitation of time-out is that it is a punishment technique. As with all punishment techniques,punishment will only have the effect of decreasing or weakening the punished behavior. Punishment will not increase or promote appropriate behavior. Increasing or strengthening appropriate behavior will require positive reinforcement techniques. Furthermore, punishment results in negative interactions between children and caregivers, which can disrupt children's mood. To avoid this negative side effect, punishment should be used sparingly and only after an appropriate reinforcement program has been in place.

Time-out does not appear to be as useful with children older that 10 years of age.

Implementation of Exclusionary Time Out:

Exclusionary time-out is a relatively technical proceedure. If implemented properly, it can be an effective management tool for reducing unacceptable behaviors; however, if not implemented properly time-out can be ineffective. The steps for implementing an exclusionary form of time-out are detailed below. These proceedures can be adapted for use with nonexclusionary and isolation forms of time-out.

Step 1: Choose an appropriate time-out

place.

Time-out from attention or other rewarding activities.

Therefore, the location of the time-out place should be relatively boring.

The student should not have direct access to toys, books, people, windows,

or any other potential reinforcement. It is often helpful to place

a chair in the time-out place to serve as a reminder to the children.

a chair in the corner or back of the room will suffice; some classrooms

are a cardboard partition or a three-sided cubicle. The time-out

place should be located where the teacher can easily monitor the

child.

Step 2: Establish the rules regarding

behavior during time-out.

In most time-out proceedures, children need to

fulfill specific criteria before they can be released from time-out.

Recomended criteria are detailed below.

|

* The teacher should determine the duration of time-out. The timeout should be long enough to be punishing, but short enough for reasons of ethics and practicality. How children will respond to time-out appears to be somewhat dependant on how long previous time-outs have been for the child. For example, time-out is likely to be less effective if it has been preceeded by a time out of greater duration (Kendall, Nay, & Jeffers, 1975; White, Neilsen, G., & Johnson 1972). A rule of thumb used by clinicians is one to

one

to two minutes in time out for

* Once in time-out, there should be no interaction with

the child for the duration

* Once in time-out, the child needs to stay in the chair

until the teacher releases

(These punishments should get progressively more severe) * Release from time out should also be dependent on a brief

period of quiet. If a

* If the child was sent to time-out for noncompliance to

a teacher request, the

|

Some children will refuse to go to time-out or will not follow the rules while in time-out. In these cases, some back-up proceedures will be needed. One proceedure is to allow the children to earn time-off for complying with the rules. Another is to add time to time-out or restrict some other school privilege for not complying with the time-out process. It also may be necessary to remove the child from the classroom to serve the time-out in another area, such as another classroom or the principal's office. As with learning any new behavior, a child's time-out behavior may need to be shaped over time. The children will likely need to experience time-out several times before they learn that the teacher will be consistent in implementing time-out.

Step 3: Communicate effectively during

the time-out sequesnce.

Punishment should follow a predictable sequence

of communication. Sending a child to time-out for noncompliance to

a teacher request should be predicted by a properly worded request and

a warning. The qalities of an effective request are outlined below.

| 1. Requests should be direct

rather than indirect. |

A direct request should leave no question in the child's mind that s/he is being told to do something, giving no illusion of choice. | Indirect request:

"Let's pick up the toys." "How about washing your hands?" "Why don't you open your book?" "Do you want to throw that paper away for me?" Direct request:

|

| 2. Requests should be

positively stated. |

Positively stated requests give the child information about what "to do." | Negative request:

"Stop running!" Positive request:

|

| 3. Requests should be

specific. Avoid vague requests. |

Vague requests are so general and non specific that the child may not know exactly what to do to be obedient. | Vague requests:

"Be good." "Be careful." "Clean up your act!" Specific Requests:

|

| 4. Give only one command

at a time. Avoid "hidden" requests. |

Some children have a hard time remembering more than one thing at a time. You do not want to punish a child for having a short attention span or for failing to remember. | Stringing requests:

"Go close the door, then turn in your papers, and then go sit in your seat." Hidden requests:

|

| 5. Request should be simple. | The child should be intellectually and physically capable of doing what you are requesting. | Too difficult:

"Draw a hexagon." (If the child does not know what a hexagon is.) |

After an effective request has been given, the

teacher should expect compliance to begin within a reasonable time.

This is called the "5 second rule." If compliance is begun within

5 seconds of an effective request, wait until the request is completed

and give an enthusiastic praise. If compliance has not been initiated

within 5 seconds of an effective request, a warning should be given.

a warning is an "if-then" statement which connects the consequence with

the behavior. Once the warning is given, the 5 second rule goes into

effect again. Compliance to the warning should be rewarded with an

enthusiastic praise. Noncompliance to the warning should result in

immediate tine-out.  Once

it is decided to send a child to time-out, communication should be brief,

clear, and direct. See the charts below for examples of effective

communication.

Once

it is decided to send a child to time-out, communication should be brief,

clear, and direct. See the charts below for examples of effective

communication.

Classroom rules should be clearly understood prior to sending a child to time-out for violating a rule.

This sequence will allow children to predict the consequenses of their behavior, thereby, allowing them to excercise self-control. Children will likele need to experience this sequence several times before they learn that the consequences to their behavior (positive and negative) will be consistent.

Step 4: Explain the time-out proceedure

to the children prior to

implementation.

At a neutral time, explain the time-out rules and what behaviors will result in time-out. Be sure to also communicate the rewards that can be earned for compliance to rules and requests.

References:

Abramowitz, A., & O'Leary, S. (1991).

Behavioral interventions in the classroom: Implications for students

with ADHD. School Psychology Review, 20(2), 231-234.

Barkley, R.A. (1990). Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment.

New York: Guilford.

Kendall, P.C., Nay, W.R., & Jeffers, J. (1975).

Time out duration and contrast effects: A systematic evaluation of

a successive treatment design. Behavior Therapy, 6, 609-615

White, G.D., Neilson, G., & Johnson, S.M.

(1972). Time-out duration and the suppression of defiant behavior

in children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5, 111-120

|

|